In Part 1 of this series, we built a foundation that underlies the indexing and dividend growth investing (DGI) mindset. In Part 2, we built on DGI further with examples of three investors, Adam, Betty and Charlie. We left a poser at the end of Part 2 about the income focus of DGI that is normally seen only with fixed income investors.

Ain’t over till the fat dividend pig squeals…

I squeal for dividends

But hey TFR, some of you may wonder….aren’t you are making a fundamental assumption that dividend income from equities (rather than their value) is important, and yet, your own results show that Adam is the ‘smarter’ one ending up with most money? Yes, but this is not a competition to be the richest guy in the graveyard. How well did your portfolio support your income needs during your retirement is more important than the portfolio terminal value. This is the crux of the DGI philosophy. You may also wonder this kind of income focus is generally seen only with bond investors and not stock investors. True, but stay with me as we build this case.

In this article, we will examine why income focus is important also for 100% equity investors, whether you choose to be an indexer or a DGIer.

Can Charlie have his cake and eat it too?

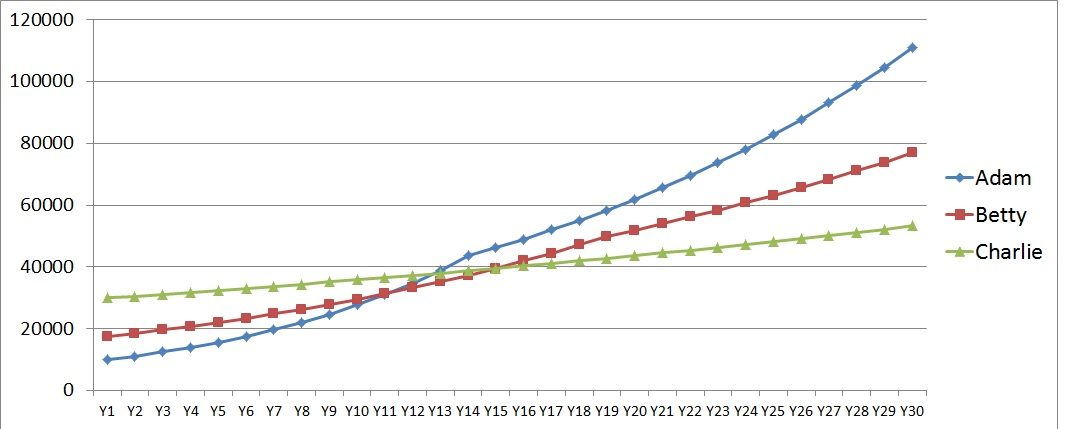

In a previous example of tempered dividend growth case, we showed an income profile for 30 years for Adam, Betty and Charlie. That chart is here.

Let’s just say Charlie lucked out with a nice company pension that he becomes eligible early at 55. Or he is lucky to find a spouse who shares his frugal DGI mindset and brings enough money into the relationship that Charlie only needs to ‘supplement’ at a level similar to Adam to have a comfortable lifestyle. In this twist, we assume Charlie only takes as much as income as Adam realizes in his dividend portfolio, but being ever the cautious DGI guy that Charlie is, he still wants the comfort of good dividend cash flow coming in. In other words, we will see Charlie following Adam’s income profile for his yearly consumption needs, and yet, has the same high yield portfolio as in the previous example.

So, for new Charlie: 6% initial yield, consuming 2% first year and increasing it by 12% yearly. Re-investing the difference back into the portfolio till dividend flow exceeds expenses, and after that, matching expenses to dividend flow.

By keeping the same high yield portfolio, and just re-investing his excess dividends for the first 15 years, Charlie has got himself a ‘permanent’ raise in his income flow for the remainder of his life. How much? If he spends like Adam in the first 15 years, and reinvests the difference, the new Charlie earns a nice 11% perennial income jump from age 69. For example, his income at Year 30 is now $59,313 instead of $53,275 earlier (11% more). Notice he didn’t change a thing in his chosen DGI portfolio, which was already slanted towards higher yield, low growth. Neither did the companies he invested in changed their dividend paths or growth rates. All he did was reinvest the dividends beyond what he spent, for the first 15 years. Reinvesting dividends gives another form of income growth that you, as an investor, entirely control.

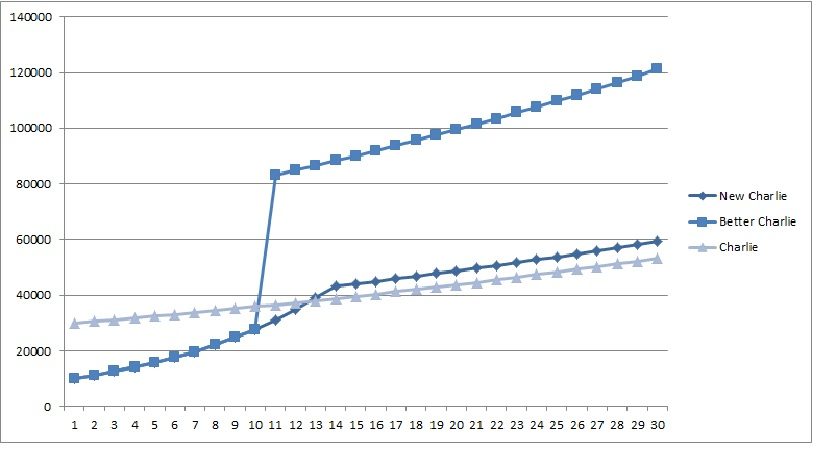

Can Charlie do even better? Let’s see. With a nice pension or a smart spouse to take care of the first 10 years of his early retirement at 55 where his income needs are much lower (similar to Adam), he can follow a similar high-growth portfolio as Adam for the first 10 years. Then, he can do a smart thing and switch over to his original portfolio after 10 years, thereby getting an enormous jump in income for the price of low future growth in his portfolio (which at 65, he can afford to). So, I present to you the better Charlie.

Because of the conscious decision he takes in Year 10 (at his age 65), Charlie moves up to an entirely different income curve, one that is far higher than even the new Charlie. This is where he gets the double benefit – the first 10 years of compounding in a high growth DGI portfolio that Adam has, which Charlie leverages after the first decade into a high income, low growth portfolio. He triples Adam’s income (2% to 6% yield) by accepting one-sixth of the future growth rate (12% to 2%) in dividends, which at age 65 might be a sensible decision for Charlie. By doing this, he has captured both the benefits of faster compounding (at a time when he could handle low portfolio income) and high income realization when he needs it (that is, a very comfortable retirement from mid-60’s). In this better path, Charlie reaches six figures in dividend income by Year 20, something he never could’ve achieved with his earlier conservative high income portfolio. Further, this income jump after Year 10 is so big that he can perhaps save a chunk of his annual dividend income and further increase the growth rate beyond the organic 2% that his portfolio delivers. So, he becomes new and better Charlie.

This enormous flexibility of a DGI mindset is what self-directed investors like Adam, Betty and Charlie can leverage to get the income flow they want at a growth rate they can manage with. Since DGI is a highly customized individual investment plan, the only way to explain the larger concept is to use generic examples on yields and growth rates. There are far too many stock permutation and combination portfolios possible in DGI that I didn’t want the larger message to get lost.

The real life experience of income growth will not be as smooth as the charts show because both dividend and value growth rates are not constant for any given stock. There is also risk of an occasional dividend freeze or cut during recessions. However, we have attempted to consider those in the ‘moderating’ growth assumptions we made in the examples. Given the variety of every DGI portfolio’s holdings, dividend yields and growth patterns, the simplifying assumptions we have made are necessary to show the larger principles of this investing philosophy.

Why is income so important even in all-equity portfolio?

By now, you may be wondering why should we focus so much on income? Income is important even if you approach a traditional financial planner who advises 60/40 portfolio of stocks and bonds. But that’s why bonds are there, right? Yes, but the problem with bonds is that their income is flat. There is no inherent growth in bond income. Income is the only return that a bondholder can expect over the long-term. What, you may ask incredulously. C’mon TFR, bonds have delivered great capital gains over the last 20 years, you protest. Yes, but let’s consider this from a really long-term (as in 50+ years) perspective and also, a future path of where do we go from here. All the capital gains from bonds – for an investor who stays the course – will slowly evaporate as interest rates rise from historically low levels.

To look at income from both bonds and equities from a long-term perspective, let’s see an interesting study done over last 90 years. I am referring to the Brandes Institute report (titled Income as the Source of Long-Term Returns, 2015), which uses data from Ibbotson Associates and other global financial data sources. I am not at liberty to attach the report here or copy its images but I will share the relevant conclusions:

Over a 20-year rolling period going back to 90 years, over 99% of total returns come only from income for U.S. bond investments. In other words, good luck counting on capital gains from bonds. For US stocks, a surprising 61% of the total returns over any 20-year rolling period come from income (dividends). Even for other developed markets, nearly half of the total returns over any 20-year rolling period were from dividends. This applies regardless of whether the gap between dividends yields and long-term bond yields is either positive or negative. In other words, dividend income is the dominant source of total stock returns regardless of whether bond yields are high or low.

Here’s the clincher. The above conclusions from the study came from using broad market indexes like S&P 500 and FTSE Developed Markets as equity holdings. In other words, there was no deliberate dividend stock focus by the study authors. Surprised yet?

So, where does that leave the debate on DGI vs. Indexing and which works better? Hang on, I am coming to that in the next article.

Raman Venkatesh is the founder of Ten Factorial Rocks. Raman is a ‘Gen X’ corporate executive in his mid 40’s. In addition to having a Ph.D. in engineering, he has worked in almost all continents of the world. Ten Factorial Rocks (TFR) was created to chronicle his journey towards retirement while sharing his views on the absurdities and pitfalls along the way. The name was taken from the mathematical function 10! (ten factorial) which is equal to 10 x 9 x 8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 3,628,800.