Jane Goodall, the legendary conservationist and animal behavior expert, changed the world’s understanding of chimpanzees. Her groundbreaking work in Tanzania’s Gombe Stream National Park reshaped wildlife research forever.

Yet beyond her extraordinary career, her personal life carried stories of love, loss, and companionship that shaped the woman the world came to admire.

A Journey That Changed Science

Goodall’s fascination with wildlife began early, but her research in Gombe turned that passion into a historic mission. Spending years in the wild observing chimpanzees, she redefined how humans view animals.

Her discoveries didn’t just advance science, they captured hearts across the globe. But amid her research success, her path crossed with two men who would profoundly influence both her personal and professional worlds.

The Meeting That Sparked a Partnership

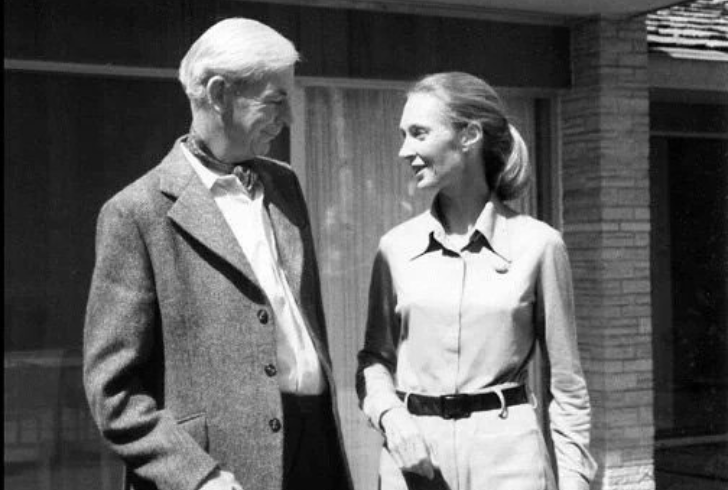

Intagram | @jgibelgium | Jane Goodall and Hugo van Lawick turned their shared love for wildlife into a lasting partnership.

In 1962, Goodall met Dutch photographer and filmmaker Baron Hugo van Lawick. National Geographic had sent him to Tanzania to document her work with chimpanzees. Initially, she wasn’t thrilled about his arrival. She worried that his presence might disturb the animals she had spent years earning the trust of.

“They wanted photos and film, so they sent Hugo,” she later recalled. “I didn’t want him to come because I was afraid the chimps would be scared and everything would fall apart.”

But her hesitation faded quickly. Van Lawick’s deep love for wildlife matched her own. His photographs brought her discoveries to life for the rest of the world, showing how similar chimpanzees are to humans. Their mutual respect grew into affection, and two years later, they married.

Love in the Wild

Their marriage, rooted in a shared passion for nature, blossomed under the African sun. They welcomed a son, Hugo Eric Louis, and for a time, their lives intertwined beautifully, science, exploration, and family all blending together. Yet as their careers expanded, the distance between them grew.

National Geographic stopped funding van Lawick’s trips to Gombe, and he moved to the Serengeti to continue his filmmaking career. Goodall stayed behind, devoted to her research and the chimpanzees she couldn’t abandon.

“He had to go on with his career,” she said years later. “And I had to stay at Gombe. So it drifted apart.”

Their separation was painful but respectful. Both recognized that their ambitions, though deeply aligned in purpose, had taken different routes. “I wish we could have carried on with that marriage because it was a good one,” she noted.

A New Chapter With Derek Bryceson

By 1972, Goodall’s dedication extended beyond her research as she joined efforts to establish a national park in the Gombe region. That mission led her to Tanzanian Parks Director Derek Bryceson. At first, she found him intimidating, having heard he was “mean and unsympathetic.” Yet their first meeting proved those assumptions wrong.

Instagram | @janegoodallinst | Jane Goodall and Derek Bryceson formed a partnership rooted in love and their shared passion for wildlife conservation.

Bryceson admired her passion and scientific precision, while she discovered a man who shared her vision of protecting Tanzania’s wildlife. Both later divorced their previous spouses and married in 1975.

Bryceson, also a member of Tanzania’s National Assembly, recalled being struck by her presence when she once presented her chimpanzee research to parliament. “She made a very definite impression,” he said.

Building a Life Together

The couple enjoyed a quieter, more private partnership than Goodall’s first marriage. They found peace in the simplicity of shared dinners and quiet evenings near the lake. Bryceson often said that an “ideal life” would be to stay at Gombe year-round, far from the bustle of city life.

Their happiness, though, was brief. In 1980, Bryceson died of cancer, ending their five-year marriage. Goodall spoke of that time with deep emotion. “He got this horrible cancer,” she said. “That was the end.”

A Life Shaped by Love and Legacy

Goodall often reflected that both men helped define her journey. Van Lawick helped the world see her research through his lens, giving global recognition to her work. Bryceson protected that very research through policy and preservation. “If I hadn’t married Derek, there wouldn’t be a Gombe today,” she once said. “If Hugo hadn’t come along, the chimp story would probably have ended.”

After losing Bryceson, Goodall chose not to remarry. She felt fulfilled by her work, friendships, and purpose. “I didn’t meet the right person again,” she said. “My life was complete. I didn’t need a husband.”

Even after heartbreak, Goodall’s life remained a testament to resilience. Her relationships reflected the same strength and empathy that defined her work with animals. Each love, though different, became a part of her legacy, one built on curiosity, compassion, and courage. Through science and personal strength, Jane Goodall proved that love, in all its forms, can fuel a lifetime of purpose and peace.