Very few purchases have as big an impact on early retirement.

We all have to live somewhere. We also need a roof over our heads. Even before the buy vs. rent argument enters the picture, what’s even more important is the allocation you give to your housing expense as a percentage of your income.

The math of compounding works in such a way that the early dog years count a lot more than the later years. So, if you want to reach financial independence or even to be considered a PAW, then you must control your housing costs.

The problem is nobody teaches you this early in your life because the real estate industry and mortgage finance industry (including banks) spend millions of dollars in advertising each year to entice you to buy or rent the biggest, best house you want (but don’t need). Not to be left behind are your peers, friends and family, whose well-meaning advice includes living in a “nice” place. Never mind the cost of a “nice” house but they see it as their ‘duty’ to make you buy the best house you can barely afford.

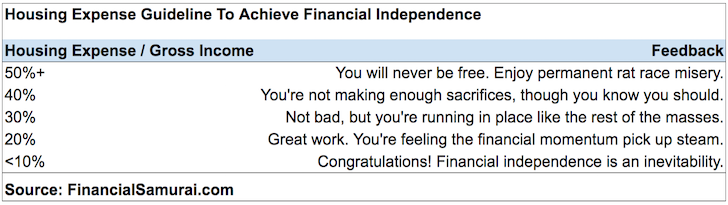

Even the banking guidelines of acceptable mortgage debt being around 30% of gross income is aimed at keeping you stuck in the career rat race forever. Many people living in expensive cities in the world shell out 40%, 50% or even more of their income in housing alone! This is a sure way to keep you house rich and possibly cash poor.

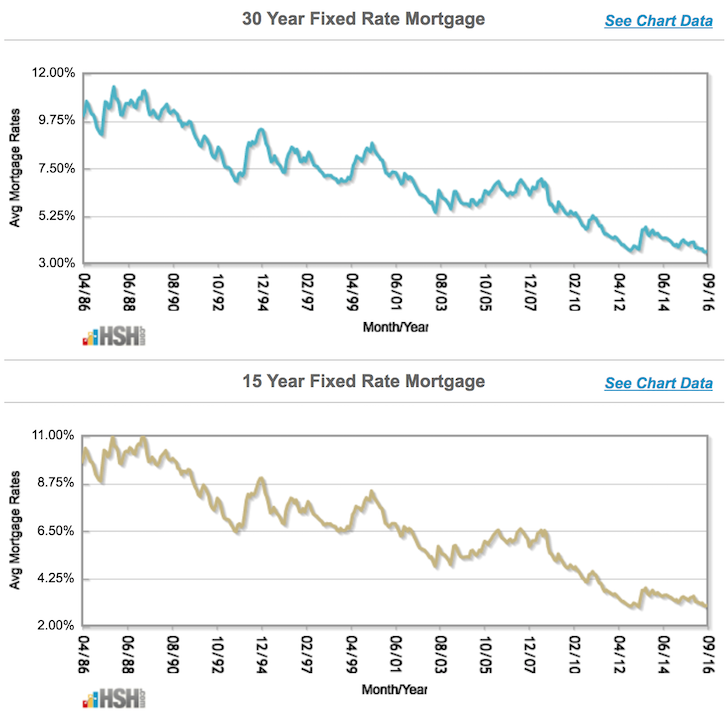

This is not helped by the declining mortgage rates over the last 25 years, as this encourages people to house up. My anecdotal research shows: [tweetthis]Every 1% decline in interest rates causes people to buy 300-500 sq. ft. more housing space that they don’t need. [/tweetthis]

Trending to an ever bigger house

Poverty not on income, but based on housing allocation

Over my four years of graduate school in a mid-western US town, my research assistant stipend reached an annual maximum of $15,000, that too in the last year. Since this was basically poverty-level income even back in the 90’s, there was hardly any tax due on that income. So, I earned a net pay of $1250 per month during my single days as a poor graduate student.

Three of us shared a nice (there’s that word again) 3-bedroom apartment that cost us $720 in monthly rent.

This was not a frugal housing choice by any means because cheaper 3-bedroom apartments were available to be had for less than $600 even then. Also, we could have easily added one more roommate as the apartment was spacious enough for four people to share. Still, being in graduate school, we all wanted our own private rooms, and only share cooking and cleaning responsibilities. On most days, the food was Ramen noodles and leftover pizza, as our graduate research kept us busy till late on most evenings. Also, this place was only a 5-minute bus ride away on a city bus route, which was free for university students.

I still remember how envious some of my classmates were about our apartment because they were living in shitty places on campus. We happily took this upscale place on rent and my share of it was $240. Here’s the key point. Despite this nice apartment, my housing costs even as a poor graduate student (earning below the US poverty level income) was only 19.2%.

This is the main reason why I never felt deprived even on such meager income. I didn’t have a car then as I never needed one – every place I wanted to go was either walk-able or a convenient bus ride away. My roommates and I only rented a car when we wanted to go to another city for a quick holiday (we never had the luxury of a long holiday in graduate school), which was rare anyway. This is yet another reason why graduate school is considered modern day slavery.

With my housing cost percentage well below US mortgage debt standards, I was actually able to save money as a student and graduate with nearly $10K of savings when I finished my Ph.D. in a demanding engineering field.

Once you get used to low allocation, you want to keep it that way.

Low allocation doesn’t mean an impractically tiny house.

Right after graduate school, I got a job as a research engineer in a company’s R&D department with a salary of $60K! I thought I hit pay dirt – this was more money than I had collectively earned or even seen in my lifetime till then.

What is the first thing you do when you get a nice job out of school? Splurge, of course. I decided I had enough with roommates and decided I should live alone. I found a nice one-bedroom apartment very close to my office that cost me $500 in rent. In other words, my housing cost went up by a whopping 108% over graduate school.

Luckily, I had the sense not to buy a new car. Thanks to my graduate school buddy who came from a family of mechanics, he drilled it into my head not to buy a new car…ever. So, my first car purchase was a used Honda Accord for $5,000, which had close to 100K miles on it.

It turned out even my housing decision then wasn’t bad. My apartment cost me $500 in rent back in 1996, and this meant my housing costs to gross income ratio was only 10%. Though I didn’t pay attention to such ratios at that time, my 108% increase in housing costs was more than offset by my quadrupling of income, resulting in an even better financial position at the beginning of my professional career. This has made a huge difference in my FI journey.

Low housing costs saved my butt big time even in other ways then. It helped me bounce back from financial screw-ups. Despite the investing mistakes I often made (like trading options, commodities etc.) with my sizable discretionary income in my late 20’s, I was able to recover quickly due to a high savings rate, thanks to my 10% housing cost to income ratio. My savings rate was routinely over 40% of my after-tax income.

This matters a whole lot because of the dog years of investing.

In the early days of your journey to financial independence or early retirement (FIRE), your net worth is almost all from savings, as there is hardly any capital gains or income. It’s like cooking over a campfire. You feed a lot of firewood initially to get the water up in temperature, and it feels like forever before it reaches a boil. After a while, you need to occasionally put in a stick or two in the fire to keep the water boiling. That’s the same way with investing.

Financial Samurai published the above interesting guideline chart on recommended housing expense ratio, which essentially mirrors my own experience in housing. You should always aim to start with 20% or less, and try to bring it to 10-15% over the bulk of your working career. At Ten Factorial Rocks, we believe in sensible instead of excessive frugality. So, while having a ratio under 10% is great, it may not be practical for many. A sustainable ratio for many FIRE-aspirants would be 10-20%. It’s not all bad if you are in 25-35% housing ratio range, as long as you work on a path to get down to 20% over time.

Figuring out your housing is the key to a successful journey to financial independence.

Raman Venkatesh is the founder of Ten Factorial Rocks. Raman is a ‘Gen X’ corporate executive in his mid 40’s. In addition to having a Ph.D. in engineering, he has worked in almost all continents of the world. Ten Factorial Rocks (TFR) was created to chronicle his journey towards retirement while sharing his views on the absurdities and pitfalls along the way. The name was taken from the mathematical function 10! (ten factorial) which is equal to 10 x 9 x 8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 3,628,800.

12 comments on “Figure Out Housing If You Are Serious About FIRE”